Editor’s Note

by Aria Kothari

Eek! It’s been a while. I missed this so much.

Scraps! – Digital is the beginning of a collection of things and stuff and tidbits. This issue will consist of fragments of days long past and pieces of personality and renewment and dreams and what is sentimental and all that is special. This issue will consist of grocery store receipts and gum wrappers and stickers and price tags and concert confetti. This issue will be a big, scrapped together, beautiful little mess.

This issue will be released in fragments. I’m feeding you scraps. Get it? You get it.

Here is just a little bit. I hope you like all this stuff.

Kisses!

xoxo,

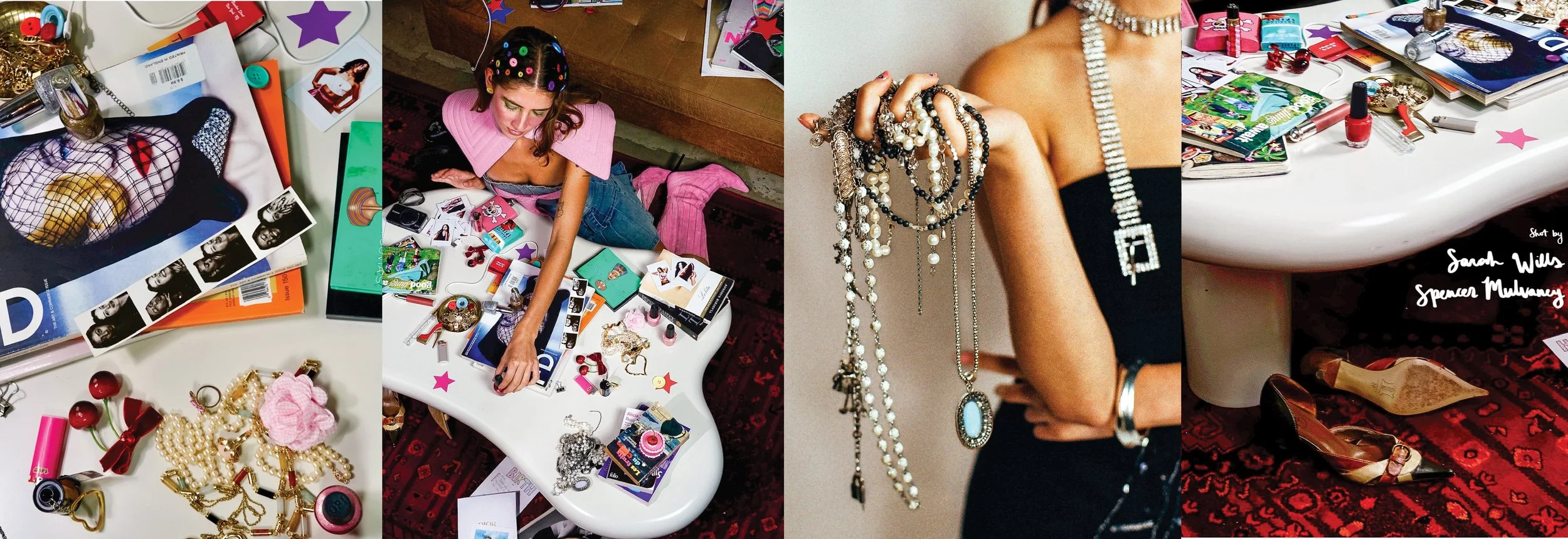

“Scraps of Self” is a three part interview series exploring the ways in which the items in our bedrooms—whether intentionally showcased or accidentally accumulated— come together to provide a detailed description of the self. Click here to join Sueah Whang, Jack Teehan, and Desmari Miller as they take us around their NYC apartments!

Wear and Tear

Luxury, Labor, and the Object-as-Archive

by Jack Teehan

Designed in 1984, the Birkin bag was created by Hermes executive Jean-Louis Dumas for the eponymous English-French actress Jane Birkin. Birkin famously told Dumas that she was unable to find the perfect leather weekend bag while on a flight from Paris to London. According to fashion legend, Dumas in return sketched out the now canonical bag on a paper airsickness bag. Today, the Birkin is more than just a bag. With prices ranging from two thousand dollars to more than two million dollars, the bag is semiotically rich, signaling to those in the know that the wearer is one of discerning taste and high status, cognoscenti of craftsmanship. Thus it’s not surprising that the cultural ubiquity of the bag is constantly amplified by celebrities, deified in the pop-culture canon.

Against the larger cultural backdrop controlled by late-stage capitalism and fast fashion, the fascination with the Birkin seems like an outlier. The same people who fetishize the Birkin also expeditiously buy and discard from Shein and Fashion Nova. There's an inherent contradiction between the cult of fast fashion that requires waste and the cult of the Birkin that prioritizes preservation. These two modalities of fashion coexisted and were personified by 2010s Kardashian culture, in which Kylie Jenner would keep pristine Birkins behind a glass case while posting ads on Instagram for SugarBear Hair and nylon bikinis. Within this dialect, care is segregated: the craftsmanship of the Birkin is worth the meticulous preservation while the craftsmanship of fast fashion is disregarded completely. Why should care be reserved only for the Birkin?

In tandem with the indie sleaze revival and the broader 2000s nostalgia boom, fueled by cultural figures like Addison Rae and PinkPantheress, there’s been a renewed fascination with Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen’s borderline abusive relationship to the Birkin bag. Their preference for beat-up, overstuffed, borderline decomposing Birkins has resurfaced in the digital zeitgeist as both a fashion moment and a kind of anti-luxury power move. It’s a gesture that reads as more genuinely “rich” than Kylie Jenner’s backlit closet of pristine Birkins behind glass. Reddit user u/Likesosmart put it bluntly: “If you think about it, a Birkin in shitty, well worn condition is the true sign of wealth.” Inspired by the Olsen twins’ bags, TikTokker Jake (@sminkytwinky), posted a video of themself distressing a crisp new Birkin by stepping and jumping on it. Reactions varied from “Love when rich people rich right!!!” and “As Jane [Birkin] would’ve wanted” to “this hurt me a lot” and, perhaps most directly, “Over time. OVER TIME”. This elaborate discourse over a generally mundane concept—wear and tear of a personal object—speaks to the cache of the Birkin in popular culture. For most people, a $10,000 bag is a life event, a milestone. For the Olsens, it’s not even scarce. The Birkin’s supposed exclusivity, with its bag quotas and sales associate gatekeeping, starts to unravel when you see it treated like a canvas tote. There’s something perverse and fascinating in the depreciation itself of a worldly possession elevated to the status of golden calf.

Mary-Kate Olsen with her Kelly bag, November 2010.

Photo Courtesy of Getty Images

Nevertheless, one really has to step back and consider the fact that all of this is kind of insane. Why is it such a radical act to simply use your possessions?

As fast fashion has poisoned people’s appetite to expect constant production and proliferation of new garments, something as mundane as a well-loved bag becomes iconic because it is rare. The cocaine-addled pace of fast fashion exists in parallel a system where consumers no longer are making purchases that will become heirlooms, whether for cultural reasons or financial concerns. Like the microplastics that leak out of our clothing, this attitude towards our belongings is synthetic. This system was invented by capitalists to keep audiences consuming over and over again, purchasing and re-purchasing the same items when they start to fray at the edges. By looking at alternative modalities of consumption, particularly those from pre-capitalist eras, we can understand how the people, particularly the mothers and daughters, of yesterday were able to survive before the industrialized state of fashion in which we now find ourselves engulfed.

If destroying a Birkin reads as a rejection of consumer excess, practices like visible mending go a step further: they reject the premise that fashion must always mean total consumption in the first place. Instead of intentionally destroying goods to simulate wear-and-tear, I hope the culture can mature to different modalities of use, re-use, and repair by examining visible mending as an alternative to contemporary consumption. Visible mending is a decorative approach to repair. Instead of hiding the damage, visible mending exposes the healing process. A combination of techniques and materials can be used to save a small hole, rip or tear, and extend the life of an item which is otherwise in good condition. Across cultures, there are long standing traditions that frame repair not as lack but as art: Victorian darning, South Asian kantha, and Japanese boro all offer models of how damage can become decorative, and how preservation can hold memory.

Darning

Darning is an embroidery technique used to repair holes or worn areas in fabric, particularly knitwear like socks and sweaters, by weaving new thread or yarn into the damaged area. The craft was taught as a regular chore to young Victorian girls. Darning aims to make new, re-new and restore by the insertion of additional threads into the warp and weft of a cloth to repair holes and tears. Chiefly, the motivation for this activity was economic, it was far less expensive to repair fabrics and garments rather than purchase new items. An assumed aim is invisibility, but the very act of darning transforms the character of the cloth as the threads are interwoven into the fabric; they impact and distort the surface becoming visible, like an embellishment or decoration on the garment. The result was often a piece that was just as beautiful as it was practical.

Kantha

Kantha is one of the oldest embroidery traditions to come out of the Indian subcontinent, with roots that stretch back to before the Vedic period. It began as a way for rural women in what’s now West Bengal, Odisha, and Bangladesh to repurpose worn-out cloth, stitching patchwork from old saris and rags. The word “kantha” refers both to the running stitch used and to the finished textile itself. It was never a royal commission or the product of elite workshops—it was a women’s practice, passed down through generations. Whether it was a landlord’s wife making an intricate quilt in her spare time or a tenant farmer’s wife stitching something out of necessity, the result was often equally rich in skill and beauty. The practice demonstrates a circular economy of production and consumption, that artisan saris could become comfortable items of domesticity.

Boro

Boro is a Japanese textile tradition that emerged out of necessity, particularly among working-class communities in the Edo and Meiji periods. It involves layering and patching worn garments, often with indigo-dyed cotton scraps, over and over again, sometimes across generations. The resulting textiles are practical, but have become rich visual records of repair, wear, and familial care. What was once seen as a sign of poverty has, over time, been recognized for its beauty and complexity, embodying values of sustainability long before the term entered popular consciousness. The textile becomes an object lesson in the history of the family, of the culture, and of production.

The fascination with the Olsen twins’ worn-out Birkins, whether seen as signs of wealth, rebellion, or exhaustion with status, exposes how much cultural weight we place on objects. In a digital moment obsessed with rarity and singularity, their bags, and the Olsen twins’ treatment of them, feel both intentional and elusive. Mending offers a quieter, more sustainable way to participate in this aesthetic, making the worn feel considered rather than cast off.

Online, the performance of damage is often about signaling individuality, authenticity, or detachment from wealth, but it rarely escapes the spectacle. The Olsen twins’ battered Birkins may seem subversive, but they still rely on the same logics of rarity and attention. Repair asks something else of us entirely. Rather than valorizing destruction as a performative gesture, we might instead look to traditions like darning, kantha, and boro. These practices reframe damage not as something to hide or fake, but as an invitation to care, to extend the life of a garment, to make repair a form of storytelling. They come from long histories of making do, of thrift, of labor and love. Though none of this is new, it feels newly urgent in the face of environmental collapse and fashion’s accelerated churn. In an era of accelerating cyclical damage and waste, repair is radical: it’s slower, quieter, and harder to commodify.

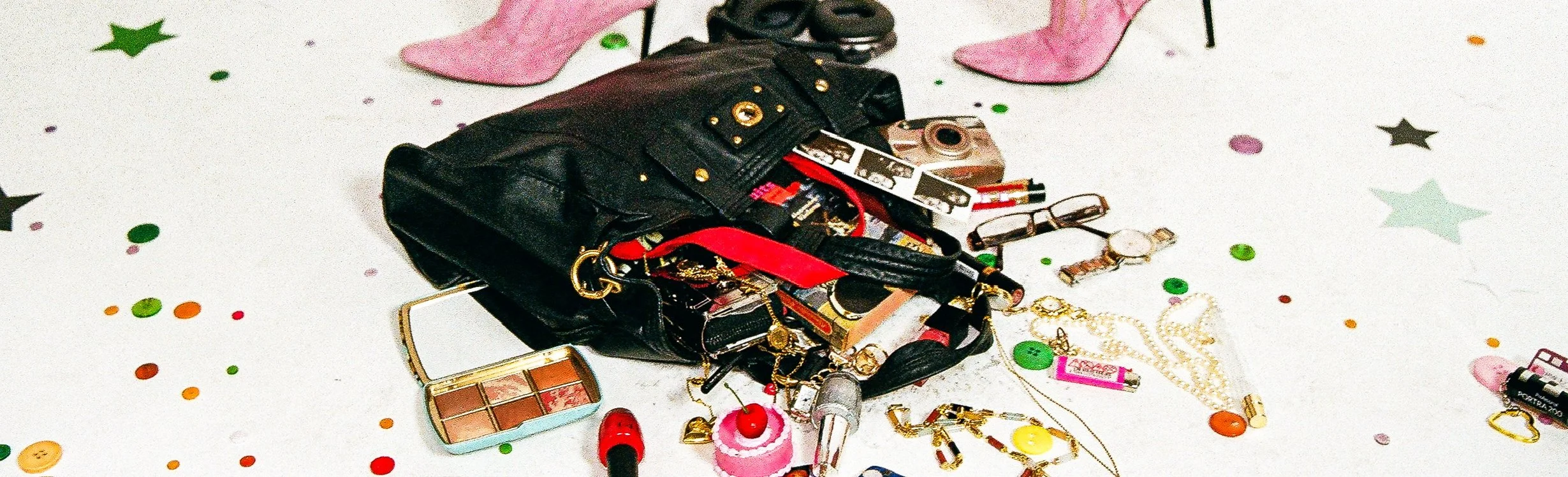

Desmari’s Scrapbook

by Desmari Miller & Aria Kothari

It would be quite silly to dedicate an entire issue to scraps without mentioning scrapbooks. Here are some of Desmari’s.

(more to come)

Acknowledgements

EIC, Creative Director Aria Kothari

Fashion Becca Solomon

Graphic Design Aria Kothari

Photography Sarah Wills, Spencer Mulvaney

Set Design Desmari Miller

Models Emelia Kelly, Sueah Whang